In architectural terms, the Game Boy is a far more advanced machine than the Nintendo NES.

Even though it was a portable console — and in some aspects less powerful due to its focus on energy efficiency — many of the lessons learned from the NES were carried over and perfected on the Game Boy. At the same time, it preserved the same development paradigms, and this was no accident. It was done intentionally, among other reasons, to make life easier for developers who had grown alongside the NES architecture and were now stepping into the new age of modern video games.

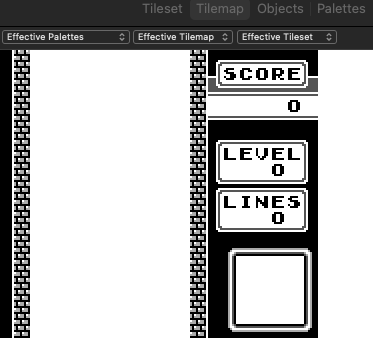

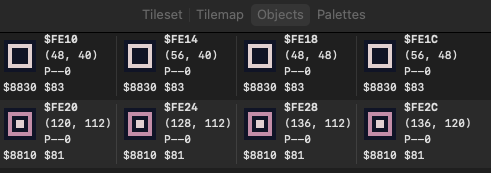

Unlike earlier machines that were closer to micro computers, the Game Boy graphics system, like the NES, had its own dedicated video memory (named vram), completely focused on processing tiles (graphic blocks of 8×8 pixels).

Under this scheme, the console could create games as rich and varied as Link’s Awakening or Kirby’s Dream Land, featuring smooth scrolling backgrounds. Alongside that fine background scroll, it also had a reserved area for actors or sprites — representing the player, enemies, and other interactive elements. There was even an alternate background layer intended for the HUD, which made life so much easier for development teams.

The console also had one advantage over the NES: its low resolution. The maximum number of sprites per screen (40, slightly less than the NES’s 64) actually covered a larger portion of the display area, relatively speaking.

There were also quality-of-life improvements, such as more precise control over the horizontal video rendering process — making graphical tricks that required a lot of effort on NES, like parallax backgrounds, almost feel like native features on Nintendo’s new handheld.

In short, the Game Boy was like a portable NES — a bit less powerful in raw terms, but completely optimized for the kind of games that were popular at the time. That’s why Game Boy programmers quickly managed to make things look easy that had once been difficult during the NES’s early days, eventually crafting genuine 8-bit engineering masterpieces by the end of the console’s life.

I think that’s what made me believe my game idea was actually possible. I looked at games like Yoshi’s Cookie and Tetris Attack (Panel de Pon) and saw them doing things that seemed similar to what I wanted to achieve.

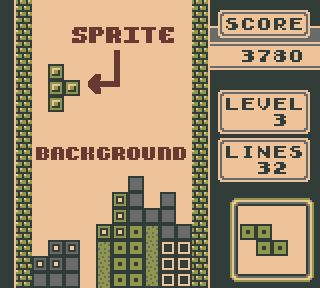

What I didn’t know was that those games were full of graphical tricks, pushing the hardware to its absolute limits — even more so than seemingly “bigger” titles like Pokémon or Zelda.

Puzzle games had never been as popular as they became after the release of Tetris for Game Boy in 1989–1990, something that, in my opinion, even caught Nintendo off guard. They quickly created the Dr. Mario franchise as an attempt to compete with the tetromino fever — or at least to ride that same wave of success.

Coming from much older and weaker machines, it wasn’t that hard to port Tetris to the Game Boy — but that doesn’t mean the console was specifically designed for that kind of game.

Still, the market had spoken: people wanted more puzzle games for Game Boy. That’s why we can find incredible feats of engineering in those titles I mentioned — games that in some ways go against the system’s original architectural intent, yet at the same time are cleverly designed around its limitations, with lessons learned from the very Tetris port that started it all.

Here’s a fantastic tutorial on how to make your own Game Boy Tetris in GBDK by Larold’s Retro Gameyard, featuring a design approach similar to what developers used back in the day.

So yeah — I had chosen a difficult genre for my homebrew project.

And to make things worse, most of the documentation and examples you can find online today focus on those “easy” genres — RPGs or action RPGs like Zelda and Pokémon, or platformers like Super Mario Land.

Those are the types of games the system was originally designed for, and nowadays there are even dedicated engines like ZGB or GB Studio that make developing them much easier.

At this point, any sensible engineer would have probably thought, “This doesn’t belong here,” and moved on — or at least reworked the idea to fit within the platform’s limits.

But I’m not a sensible engineer.

In fact, I’m not really an engineer at all.

Follow me in this mad adventure in the next entry of the blog, where we’ll once again try to make my game possible on the Game Boy.

Resources mentioned:

Larold’s Retro Gameyard · ZGB Engine · GB Studio